St. Patrick’s Day has symbolized various things throughout history: the conversion of the native Irish to Christianity, a way for Irish immigrants to celebrate their heritage, an excuse to get drunk off green beer, etc. Yet on the tiny Caribbean island of Montserrat, it also celebrates a slave rebellion. As a matter of fact, St. Patrick’s Day is such a big deal on this island that it’s one of two places in the world outside of Ireland (the other one being Newfoundland) where it’s a public holiday. Montserrat’s connection to the holiday, as well as to Ireland, may surprise you.

St. Patrick’s Day has symbolized various things throughout history: the conversion of the native Irish to Christianity, a way for Irish immigrants to celebrate their heritage, an excuse to get drunk off green beer, etc. Yet on the tiny Caribbean island of Montserrat, it also celebrates a slave rebellion. As a matter of fact, St. Patrick’s Day is such a big deal on this island that it’s one of two places in the world outside of Ireland (the other one being Newfoundland) where it’s a public holiday. Montserrat’s connection to the holiday, as well as to Ireland, may surprise you.

In the early years of the English Caribbean, a large percentage of the population was of Irish origin. Tensions were high between the English and these Irish, the majority of whom were Catholic. In 1632, a group of Irish settlers left the English colony on St. Kitts and settled the uninhabited island of Montserrat. The island gained a reputation as a “safe haven” for Irish Catholics in the Caribbean and attracted many Irish settlers throughout the 17th and 18th century, many of whom were transported there as political prisoners after Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. While the Irish had a noticeable influence throughout the English Caribbean, on this small island, where they made up more than half of the population by 1678, it was particularly pronounced. Both the island’s white and black population spoke Gaelic into the mid-19th century, and as these populations mixed, there emerged a unique mixed-race population that calls themselves “Montserrat Irish”. To this day, maps of Montserrat are dotted with toponyms like Sweeney’s Well and Kinsale, and last names like Kelly and O’Brien remain common.

Yet at the end of the day, Montserrat was much like the rest of the Caribbean: a plantation economy based around sugar and reliant on slave labor. As planters on Montserrat imported large numbers of slaves, the demographic makeup of the island shifted dramatically; while the island was 74% white in 1678, just 50 years later that number had gone down to 16%. Life on Caribbean plantations was hard to say the least; harvesting and processing sugar is labor-intensive, back-breaking and often dangerous work. White slaveowners were vastly outnumbered by their black slaves (on some islands by as much as 18 to 1), so slave rebellions were a constant fear. Although planters imposed tried to deter their slaves from revolt with harsh punishments for various infractions, it didn’t always work. In 1768, the slaves of Montserrat planned a rebellion for St. Patrick’s Day, when their Irish masters would be too distracted drinking and celebrating (some things never change) to stop them. Yet the plan was leaked, and authorities responded with swift and harsh punishment.

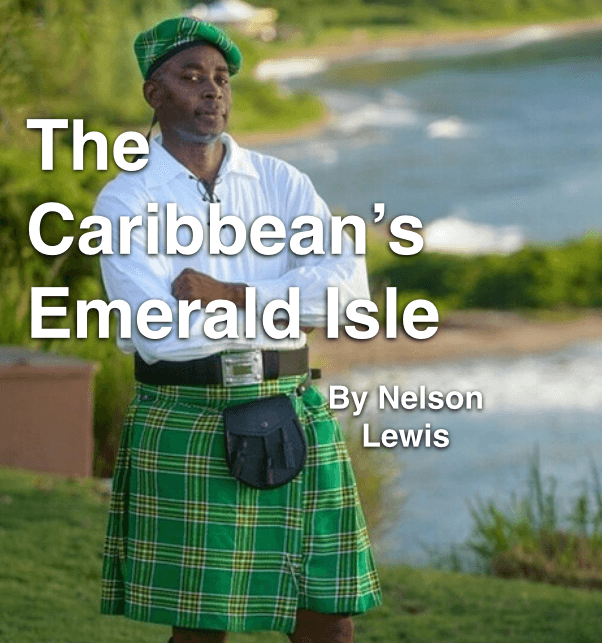

While the Irish have always played an important part in Montserrat’s unique heritage, the island began to play it up starting in the 1970s as part of an effort to attract tourism. St. Patrick’s Day has evolved into a week-long celebration with parades in “national dress” (a tartan pattern based off the Irish green/white/orange tricolor), a road race, dancing, pub crawls and public lectures. These celebrations are just as much about honoring the island’s Irish heritage as it was remembering the legacy of slavery. For example, one part of the parade involves a dance meant to mock the Irish Catholic slave-owners, where dancers carry whips and wear tall hats reminiscent of bishops’ mitres.

Even if it’s hammed up to an extent, the Irish legacy on Montserrat can’t be denied. Nonetheless, feelings about it remain mixed; while many Montserratians have at least partial Irish ancestry, it’s also a legacy tied with slavery and oppression. Irish masters were just as harsh as their English or French counterparts, handing out punishments that were just as common as they were severe. To this day, having a last name like Riley or Galway could mean you have Irish ancestry, but it could also mean that one of your ancestors was a slave with an Irish master. Yet for the people of Montserrat, while this legacy is mixed, it’s also an important part of their heritage, one that they recognize and wish to if not honor then at least understand and accept, since it’s such a large part of their national identity.